Welcome!

Randolph native honored in new documentary

ASHEBORO — To say that A.E. Staley was to soybeans and cornstarch what Henry Ford was to automobiles wouldn’t be a stretch. The Randolph County native took his third-grade education to Illinois and founded a company that became an agricultural empire.

And in his spare time, he founded a football team that became the Chicago Bears.

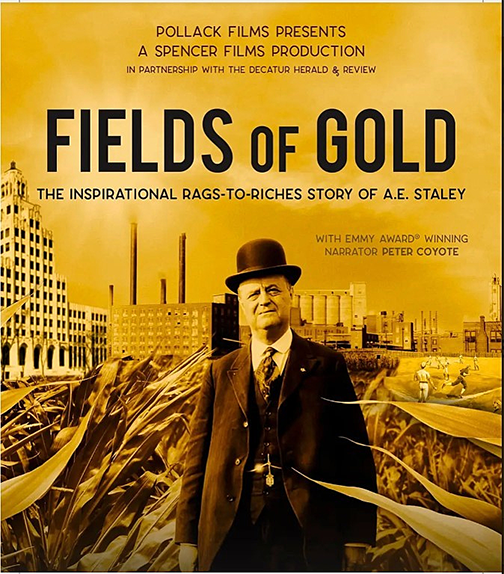

The life of Staley, from barefoot farm boy to industrial icon, is documented in the film, “Fields of Gold: The Inspirational Rags-to-Riches Story of A.E. Staley.” The North Carolina premiere will be at Asheboro’s Sunset Theatre on Jan. 14, with showings at 2:30 and 6 p.m.

Tickets can be purchased for $10 (cash only) at Brightside Gallery, 170 Worth St., Asheboro, or online with the film’s trailer at http://tinyurl.com/y9x3sxa8.

The online purchase charges $3.39 for taxes and fees.

Local sites featured in the film include:

— The Patterson Cottage Museum and Shiloh Methodist Church in Liberty.

— The original Staley Farm in Julian and Climax.

— Whitaker Farms in Climax.

Other sites from Chapel Hill are in the film.

A local great-nephew of A.E. Staley who is featured in the film, Rev. Randy Garner, will be in attendance.

The film is written and directed by Julie Staley of Staley Films, wife of Mark Staley, a great-grandson of A.E. Staley.

The documentary is narrated by Emmy Award-winning actor Peter Coyote, whose credits include narration of the Ken Burns films “National Parks,” “The Roosevelts: An Intimate History” and “Country Music.”

Staley was born in 1867 to William and Mary Jane Staley and he grew up on their farm on what’s now Old Red Cross Road between US 421 and NC 22. His father wanted Gene to become a minister or continue working the farm. But at age 14, after selling an entire wagonload of produce in Randleman, he proclaimed, “I’m going to be a businessman.”

A year before that, a missionary from China had come to a camp meeting nearby, bringing with him a basket of soybeans. Gene planted several rows of them, picked them and planted some more. Years later, Staley Manufacturing pioneered the processing of soybeans.

After several years as a traveling salesman, Staley decided to go into the starch business. He packed starch at night and sold it during the day. A decade later, after moderate success, he bought an inactive starch plant in Decatur, Ill., and the A.E. Staley Manufacturing Co. eventually became the second-largest processor of corn in the United States.

Staley was not only an innovative industrialist, he was also ahead of his time in employee relations. A press release by the producers says, “The documentary vividly portrays Staley's unwavering commitment to his employees, his customers and his community. Throughout his career, Staley demonstrated selflessness and compassion, going above and beyond to take care of his workers during a time when social support systems were lacking.”

Although Staley hadn’t had the opportunity to play sports while working on the farm, he was an enthusiastic sports fan. During a time when his business was growing, in 1919 he formed the Staley football and baseball teams, hiring athletes who would work in his factories and then play ball. One of those was George Halas, who became a player/coach on the football team.

Both teams were successful but playing in Decatur’s 1,500-seat stadium limited Staley’s income from ticket sales. He decided to turn the football team over to Halas, who would move it to Chicago. The stipulation was that the team would remain the Staleys the first year.

After that first year, Halas changed the name to the Bears, since Chicago’s baseball team was the Cubs, and football players are bigger, was the explanation.

Even today, however, the Staley origins are remembered as the Chicago mascot is “Staley da Bear.”

After Staley died in 1940, his son A.E. Staley Jr., took the company helm until 1988, when Tate & Lyle acquired 90 percent of the business for $1.42 billion. Not a bad return for a barefooted farm boy from Randolph County.

•••

Randy Garner said he grew up on the same farm as his famous great-uncle and lived in the same house. But he had little knowledge of Staley. “All I knew was that I had a great-uncle in another state who was quite successful,” Garner said.

During the last few years during travels across the country, however, Garner said he “ran across one of his places in Lafayette, Indiana, one of his plants that’s still operating.”

As Garner became more informed about Staley Manufacturing, he came into contact with the Staley Museum in Decatur, Illinois. He learned that museum officials, including Mark Staley, a great-grandson, and his wife Julie, were interested in having items from the North Carolina branch of the family. Garner said he’s donated a hutch that had belonged to Gene’s sister, and a large dining room table that’s been in the family for more than 100 years.

During his visits to Decatur, Garner said, he’s talked to people in the area who were familiar with Gene’s legacy. “He was a man very concerned about his employees and about his customers. That’s probably why he was as successful as he was.”

Even the City of Decatur benefitted from Staley Manufacturing and the man who founded it. “What he did for Decatur was phenomenal,” Garner said. “The city might not be there if not for him.”