Welcome!

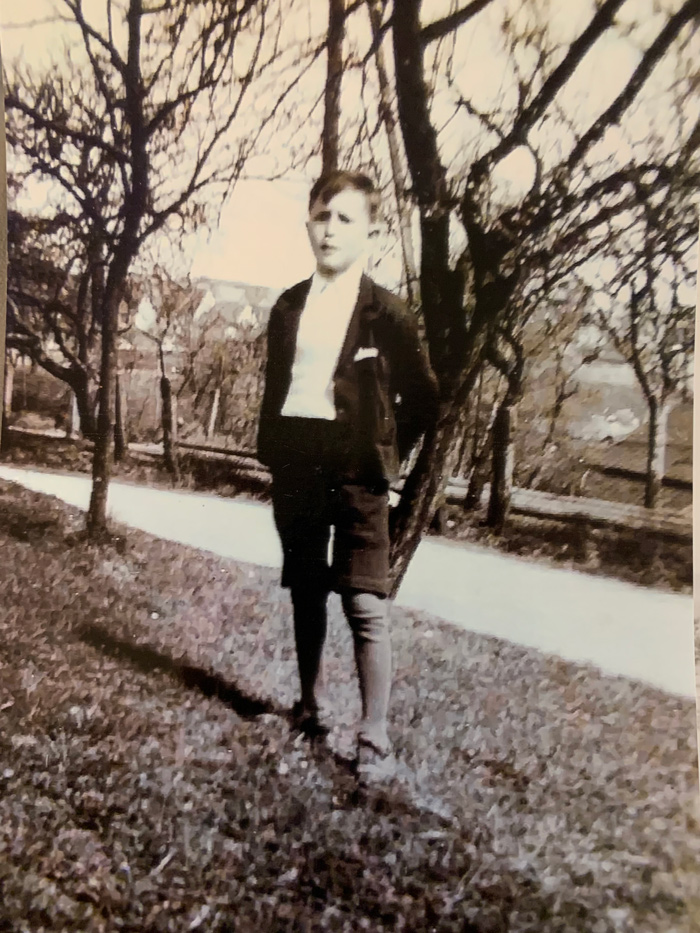

‘Wolf’ takes a look back nearly 90 years ago to recount growing up in Germany during World War II.

Growing up on a different side of history

Imagine you are a young boy growing up in Bavaria, Germany, and World War II is unfolding.

The community you were born in, Schweinfurt, has become a training ground and large industrial production area for the German army. Your mother sends you to stay with a family, away from the city.

Your father joins the war effort as a master mechanic for the German army and is stationed in Nuremberg, Germany. There is new hope within him as most people feel Germany will be victorious.

You are adjusting to life with a different family. They do their best to welcome you, but worry of having another person to protect and feed in war.

You want to be good and help the family with chores.

But at night, when it’s quiet, you lie in bed wondering what your father is doing. You miss and worry about your mom, your siblings and those German SS soldiers. They seem scary and mean, and you dream about a new life, somewhere far from here.

You are tired, need to sleep and finally drift off to sleep where it feels safe, for a little while.

___

This storyline would make a great screenplay for a movie.

But for Wolfgang Hagemann, or “Wolf,” it is a movie that never completely fades from his mind. The years are more jumbled now and trying to share them with someone younger, who wasn’t there, isn’t easy.

Today, the 90-year-old lives in Winston-Salem, with his second wife Brenda. “Wolf” is a friend to my father (Jim Canter) and has shared memories of World War II with him several times, as they both share an interest in history.

Wolf’s story needs to be shared, and he does what he can to remember.

Home was an Allied target

“Wolf” Hagemann was born Sept. 1, 1931, in Schweinfurt, Germany, a city about 200 miles southeast of Berlin.

Growing up in Bavaria, the largest land state of Germany known for its incredible scenery, festivals (including the Oktoberfest) and rich culture, are not things Wolf speaks about as he opens up about his childhood and adolescence there.

Scheinfurt was a major target for Allied bombers. Its factories produced ball bearings which were essential for the production of German tank and aircraft during World War II.

According to www.AirForceMag.com, the German aviation industry used 2.4 million ball bearings a month. Production of them was concentrated in Schweinfurt, where five plants manufactured nearly two-thirds of Germany’s ball bearings and roller bearings. Between 1922 and 1943, the surge in manufacturing tripled the population of Schweinfurt to 50,000.

Wolf’s mother, like many anxious parents of the day, sent her son to live with friends in the nearby village of Trimberg. He was about 7 years old and boarded a train to live with the Mayor (of Trimberg) and his wife.

Wolf’s mother chose this path for him to protect him. He attended school in Trimburg, and his grandmother (his mother’s mother) stayed there, also.

Changing families again

A couple years passed, and Wolf, around 9, probably had hopes of returning home. But it was still unsafe, so his mother had him picked up by another couple, Emil and Mari Gossman of Grestal.

Grestal was a small village about 16 kilometers (or about 10 miles) from Schweinfurt. It was a Catholic community, Wolf explained.

“It had 500 people, 500 houses, one mayor, one church, one priest and two schools,” he said. One of the schools housed 15 or 20 Belgium and Danish prisoners.

Wolf lived in Grestal with Emil, Mari and their two teens, Colette and Wilhem, from 1940 to 1946. The family operated a small farm, and had cows, goats, apples, cabbage and potatoes.

“The farmers stored up food for the horses,” Wolf said, “cabbage and potatoes in wooden barrels that would hold 100 liters.”

“They had lots of apples,” he continued. “They stored them in the cellars, close to the barn in a cool area.”

The apple cider he liked, and laughs recalling American soldiers drinking too much of it and getting sour stomachs.

Wolf attended school in Grestal, along with the Catholic church where he was an altar boy. He also helped on the farm and raised rabbits. “I had 75 rabbits at one time,” he said, with amusement.

Wolf remembers when Wilhem was drafted into the German army. “He was sent in or near France first, then to Russia,” he said. “He was trained to shoot tanks with heavy machine guns. You know France fell to Germany in just four weeks.”

Wilhem never made it home from Russia.

‘Black Thursday’

Wolf also remembers the day Allied forces bombed Schweinfurt, a day that became known as “Black Thursday.”

Allied Forces believed bombing the ball bearing plants would have a direct impact on the production of German war planes and tanks, thus ending the war earlier. But the German Luftwaffe were prepared for battle, and the Eighth Army lost 601 men on Oct. 14, 1943. Of the 601 crewmen lost, 102 were killed. Most — 381 of them — were taken prisoner, while others evaded capture, were interned, or were rescued from the sea. (www.airforcemag.com)

Wolf remembers visiting Schweinfurt after the bombings ceased. “Smoke was thick,” he said. “There were cows on the ground. I remember it in the German newspaper that they (Allied bombers) got delayed in England, and the Germans had time to re-fuel and re-arm. … It was good for German morale,” Wolf said, solemnly. “But it was bad for the Americans.”

“Black Thursday” was the United States Army Air Force’s (USAAF) last strike on targets without friendly

fighter escorts. The escorts turned back at the German border, and the bomber formations fought a running battle alone against the Luftwaffe. The bomber crews faced heavy flak over the target and then had to fight their way back across central Europe. Of the 291 bombers that departed on the mission, 60 were shot down. Of the bombers that returned, 17 crashed in England or were scrapped, and 121 needed repairs — and many of these aircraft brought back wounded and dead crewmen (https://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/Visit/Museum-Exhibits/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/1519661/black-thursday-schweinfurt-october-14-1943/).

‘It was our D-Day’

For Wolf, the American & Allied forces were heroes. “D-Day” in the Grestal village — the day the American forces liberated the Schweinfurt area — was in April, 1945.

“It was our D-Day, and it was a great day,” he said.

He remembers it well. Colette woke him telling him to come quickly. She said there was an American observer in the church steeple.

He recalls German SS soldiers walking down the street, and some stopped at their house. Mari gave them some water. They said nothing and left the village. The war was officially over for Wolf and the Gossmans and the Schweinfurt residents.

“It was our D-Day,” he said.

Wolf observed and interacted with the American soldiers in the village, and some of them moved into the Gossmans’ home. Wolf ran errands for them for extra money.

He loved their uniforms, especially the shoes.

“Those big, loud German boots!” he exclaimed. “It’s no wonder they lost the war,” he joked. “The Americans had soft shoes, and you couldn’t hear them coming like the Germans, and I really wanted some of those soft shoes.”

Path to American citizenship

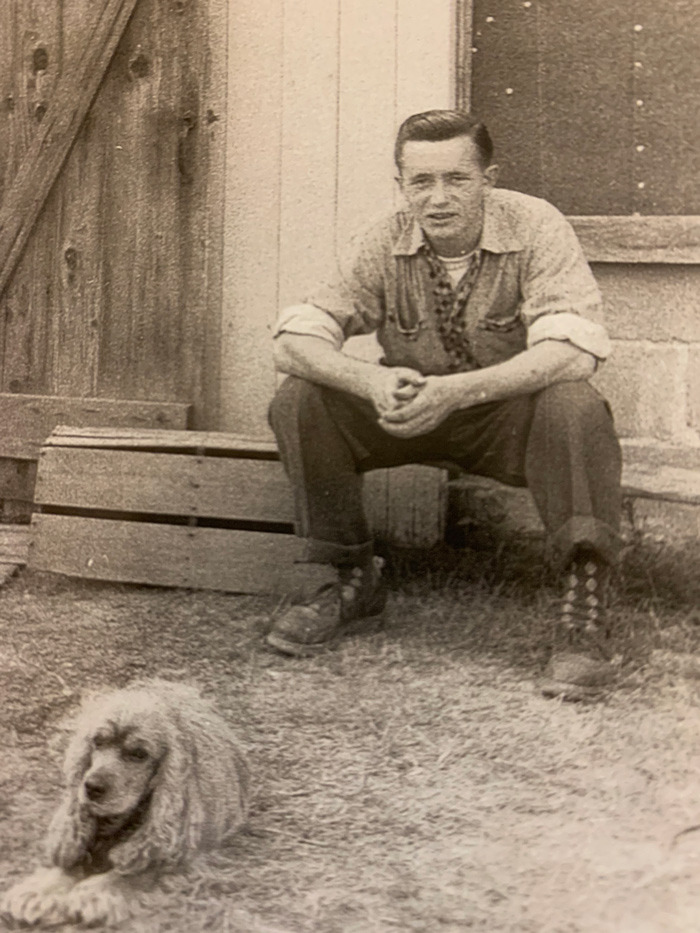

With the war over, Wolf was able to go home, but his parents had gone their separate ways. He lived with his father and his new step-mother in Grestal from 1946 to 1949, but his father was changed. He was taken prisoner of war by the French armies, and that frightful experience affected him adversely, leaving him bitter and angry.

Wolf worked for Opal, which was owned by General Motors, and in 1950, he moved to Jacobsweiler, Germany, to be close to his mother, who also remarried. He lived with his girlfriend’s family, and in 1955, they were married, and had two daughters.

Wolf’s admiration of the American clothes and shoes never fully disappeared, and he finally was able to get his own. At Opal, he earned an Apprenticeship in Auto Mechanics, and then went to work on American cars for the U.S. Army for two years. He also worked for Counter Intelligence for the U.S. Army for a year and a half. He gained valuable skills that helped him eventually leave Germany for Canada.

“I had $40 to my name and flew to London,” he said. He then moved to Ontario, Canada, and began working for an outdoor advertising company. It was 1957, and Canadians were looking for people to move there, shared wife Brenda. Wolf’s family later joined him.

In 1960, Wolf and family moved to Winston-Salem as their friends, Robert and Phyllis Carwell, lived there.

Robert rented a room from Wolf’s mother while he was stationed in Germany, and they remained in touch.

Wolf and family needed a sponsor to move to the U.S., and Robert knew Grady Allred, the original owner and founder of K&W Cafeteria.

Allred sponsored the Hagemann family, and they lived with the Allreds for approximately 6 months. Wolf worked at Hanes Hosiery for a short time and then returned to being an auto mechanic at Flow. Later he opened his own foreign car garage and operated it for close to 20 years.

On June 10, 1966, Wolf became an American citizen, and he went back to Germany through the years.

Schweinfurt became a stronghold of the U.S. military after the war ended. The tank barracks, renamed Ledward Barracks in 1946, became the headquarters of the newly founded U.S. Army Garrison Schweinfurt (USAG Schweinfurt). The U.S. Army took over the Luftwaffe Airfield as Schweinfurt Army Heliport and renamed the air base to Conn Barracks. They were expanded into large barracks with many hangars, administration buildings, a large event hall, church and sports facilities. At its peak,12,000 people made the base their home. It was closed in 2014. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/U.S._Army_Garrison_Schweinfurt).

Still grateful today

Wolf has been married to Brenda since 1980. They have visited Germany “three or four times” together.

“The country is beautiful,” she said. “The architecture is awesome. The German people really keep the villages clean. I did not see people throw trash in the streets. Most everyone speaks several languages.”

She loved the clean beauty of the mountains, visiting the castles and the history found everywhere. “There is just so much natural beauty to appreciate,” she said.

Brenda also shared about Wolf’s family.

His mother, who worked at the Post Office and was also a seamstress, passed away about 15 years ago, plus or minus, and his father died while he was on a plane on the way back from his mother’s funeral.

He has a brother who lives in Jacobsweiler, Germany, with his wife, Heidi. They were both school teachers, and have a son Frank who is a pilot for Lufthansa, one of the largest airlines in Europe.

His older brother Heinz passed away Nov. 4, 2012, and had two daughters. His half-sister still lives in Nuremberg, Germany, and has two sons.

Wolf’s two daughters, Elfi Haddock and Kirsten Harper, have given him four grandchildren. One daughter lives in Winston-Salem, and the other passed away almost three years ago.

Wolf has lived an amazing and full life. The sacrifices by many people to keep him safe as a boy and adolescent during a World War are forever etched in his memories. And to the young American and Allied soldiers who liberated many Germans from their own personal wars, Wolf is grateful.

— FROM THE AUTHOR — Thanks to my father and Brenda who helped gather information from Wolf for this story. And thanks to Wolf for agreeing to share it with us.