Welcome!

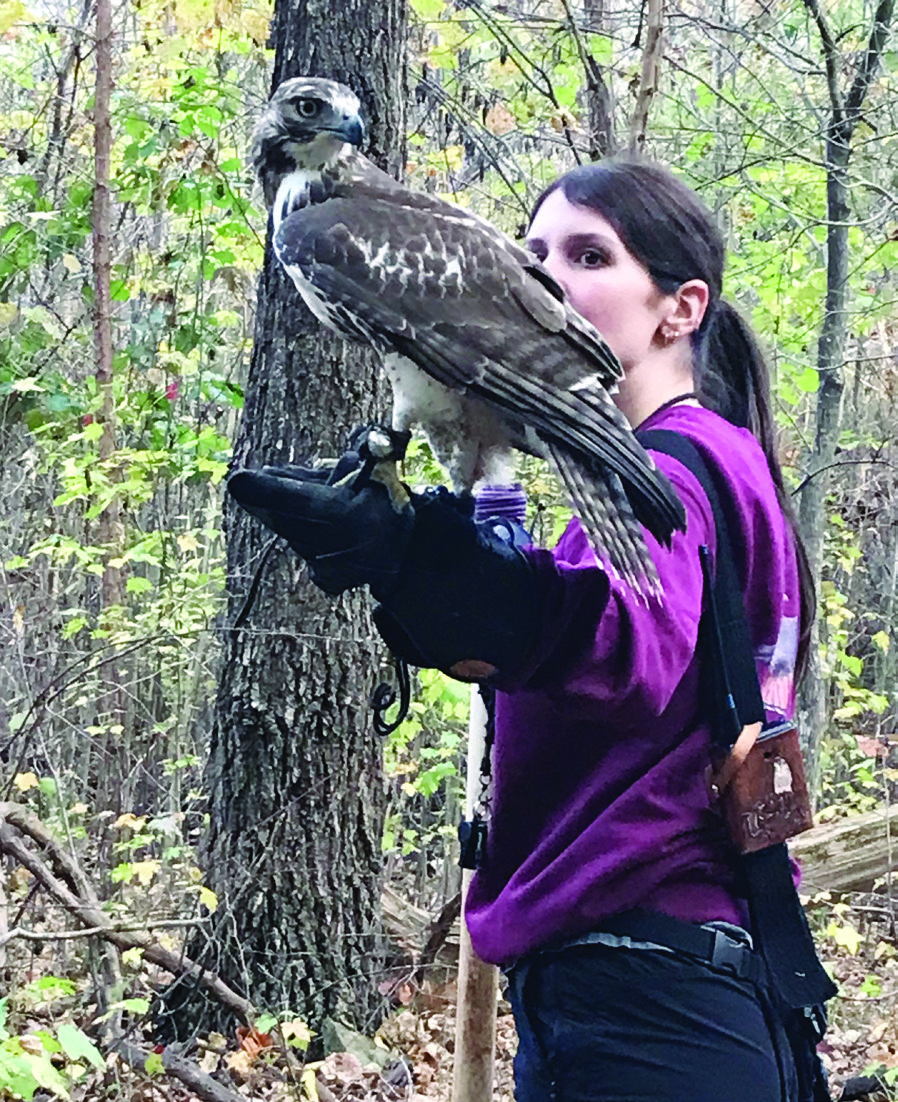

Michael Moore and Jackie Barry set out to hunt for squirrels with their hawk. (Photos: Janet Imrick / Randolph Hub)

Hunting with Hawks

Michael Moore and Jackie Barry’s favorite part of the day begins a couple hours before sunset. They spend their evenings tramping through the woods, seeking out squirrel nests in the dimming light, and listening to the tell-tale jangle of their bird of prey closing in on a kill.

“You got squirrel hawk neck yet?” Barry joked after craning her neck to see up into a tree for several minutes on Saturday, Oct. 25.

Once they spotted a squirrel, they plunged deeper into the brush with shouts of “Ho, ho, ho!” For generations of falconers, that’s been the universal signal that a squirrel is in sight.

Since the couple moved to Asheboro last year, they’ve been scoping out wooded areas with lots of acreage to take their red-tailed hawks hunting. The birds can eat all kinds of rodents and more — they’ve even seen hawks go after feral pigs — but they focus on squirrels.

“It’s the most sporting, fun, three-dimensional-type hunt you can really do with red tails,” Barry said. “People hunt jackrabbits out west. A lot of people here in North Carolina hunt cottontail rabbits. But 99.9 percent of the time, gray and fox squirrels is what we love to hunt.”

Hunt for the right partner

Barry was introduced to falconry by a teacher who started a program at her high school. She went on to intern at The Hawking Centre in Kent, England, and learned all about raptor husbandry and training.

Because it’s a niche sport, a lot of research and networking occurs online. Using Facebook, she first hit up Moore to ask about buying a falconry hood.

Moore grew up hunting in Alabama and took up falconry as a personal challenge. “I’ve always tried to push myself farther and farther,” he explained. “A lot of people, when they first start squirrel hunting, they start with a shotgun, and then they move up to a .22. I was like, ‘Well, what can I do to push myself even farther?’ And once I learned that you could take red-tailed hawks and hunt squirrel with them, I was hooked.”

That Facebook interaction led to more conversations, then visits in Alabama. “I asked if she wanted to go trapping and haven’t been able to get rid of her since,” Moore said.

“It’s nice to have a partner with such a deeply ingrained, shared passion,” Barry said. “We both want to be doing the same thing, rushing home from work, getting the same enjoyment out of it.”

Training for humans and hawks

Raptors are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Getting a hunting permit takes years. Moore and Barry had to be sponsored by a falconer, take a state exam, and complete a two-year apprenticeship.

“Here we have the North Carolina Falconers Guild,” Barry explained. “You can go to these meets and events that the club puts on and hook up with a sponsor that way. Maybe go out for a season beforehand, so you can see what it’s like, how much effort is required. Then you build your mews, which is your hawk house. You get it inspected by the state. You buy all of your equipment, and that has to be inspected, too.”

Under regulations, they can only capture hawks that are no more than a year old. Juveniles, according to them, have a 70 percent mortality rate. The female hawk they’ve been training this season was struggling to sustain herself on mice when they trapped her. They’ve honed her skills in catching squirrels, which are larger with more fat.

Like people, each hawk has a unique personality. Their current bird is very easygoing around people. Moore said it takes time to figure out how they’ll work together, sometimes at the risk of taking a talon to the face. “We’ve seen some that have more of a tender personality versus some that’ll want get a little ornery quicker,” he said.

Hawks trained by falconers typically have their mortality rate drop to 30 percent once released.

The thrill of the hunt

On the Oct. 25 hunt, Barry and Moore released the hawk into the trees around 5 p.m. She wore bells on one claw and a GPS tracker on the other. They resisted using a tracker for several years, but now they find it incredibly useful if she flies out of sight.

“I’ve almost tripped over my bird, looking for her, on a squirrel that she was covering,” Barry said. “They’re made to blend in with the leaves.”

They said that the hawks do not become so attached that they become dependent on humans for food. However, they can assist by tugging vines and vibrating the nests or by covering the base of the tree to trick the squirrel into moving into the hawk’s line of sight. Barry will strike the tree trunk with a stick. Moore made the stick for his girlfriend. He carved it from hickory, a dense and sturdy wood commonly used for tool handles like the ones he sees at his full-time job as a supervisor for Aberdeen Carolina and Western Railway.

But even with keen eyesight, powerful talons and her trainers’ assists, this evening went without a catch. Squirrels have evolved to escape as much as hawks have evolved to hunt. Competition can be an added challenge. Their hawk got rattled when a wild adult hawk swooped in and tried to go for the same squirrel.

As the sun went down, she feasted on mice provided by Barry and Moore. They do not keep any of the catches for themselves. Squirrels she doesn’t eat right away are stored to keep her well-fed when she’s molting.

Wildlife advocates

Falconry takes tremendous commitment. Barry said you must love it as much as the bird loves it. “They want to fly, and they want to hunt,” she said. “You need to be able to be okay with observing this dramatic and sometimes cruel dance between predator and prey.”

There are other ways for people to get involved without hunting. Barry also advances the welfare of wildlife through her work for Conservation Science Global. She leads a free non-lead ammo distribution program. Their goal is to cut down on lead poisoning in birds that eat carcasses left by hunters.

“There are so many man-made anthropogenic threats to raptors today,” she said. “Electrocutions from power poles, getting hit by cars, window collisions, lead poisoning, disease. So, if someone still wants to work with raptors, I would encourage them to look into rehabilitation.”

In 2012, Barry was interviewed about falconry by The Huffington Post and even approached about doing a reality show. That didn’t pan out, but they’ve since found an audience on YouTube, where they started the channel “The Squirrel Hawker.” Moore first proposed recording their hunts to review later. He compared it to a coach filming his team’s plays to improve their game.

“I started taking small clips when I saw something pretty cool happen, that I would post on Facebook, and everybody was like, ‘Please, don’t stop,’” Moore said.

For anyone interested in falconry, he said it starts with lots of research. “Don’t try to jump in feet first,” he said. “It’s very beneficial to hunt a season with a falconer, learn a little beforehand. Have your pre-flight checklist. Check all those things off the box. And if you’re okay with it, then definitely try to get into it.”